I said goodbye to

the farm yesterday. Everyone is likely to leave in the next three to four months; the landlord has requested an exit strategy, for the distance between what he wants done with the land and what the community want to do with the land is too great. The community wants to run events there and produce food to sustain themselves and their visitors: the landlord wants them to just farm tons of veg for his farm shop in Bristol. The community aren't really interested in being farmers. Yesterday was a sad day, for the group have put their love and sweat into that place for a year and a half, and now they have to leave, and all their lives will change, because a man who owns more than they do wants something different to them.

Such is the world.

I once stayed in the welsh B&B of an ex farmer named Marcus Lampard, who wanted to start a website named farmingisfucked.com.

Radford Mill was the first time I've helped out in a garden for commercial production and it had a totally different feeling to a garden producing just for the community.

In producing food for the community at Embercombe or Findhorn for example, there is a feeling of something like love in what you're doing because you're helping to make delicious, healthy, sustainable food for people you know and care about.

Why should that sense stop simply because you have never seen the face of the person who will eat the lettuce you're picking? At the Mill, I was trying to imagine the tables that the salad bags I was making, complete with delicious organic mixed leaves and decorated with blue and orange edible flowers, borrige, nasturtiums, marigolds - beautiful! At least when picked. Wilted probably by the time they're eaten unfortunately... Anyway, I was trying to imagine the people that would eat them and thinking, why can't my feeling of delight in producing food extend to these people I will never meet?

It can, I thought, but I don't like this because we're selling wholesale to a landlord, the relationship with whom is widely perceived here as exploitative, and that makes me an exploited agricultural worker right now, and that's the last thing I ever wanted to be.

And that's only participating in the system at one remove from a farm shop fifteen miles away, working in a beautiful place with nice people. How must people feel producing food on a massive non-organic farm for Tesco? Putting in a lot of effort for virtually no money in return?

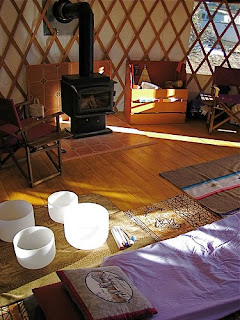

I've done a lot of shitty work at the Mill. I took down yurts after a big party (heavy and dull work that took a team of 5 an entire day), and dealt with the party's rubbish (disgusting, and formed my resolve to live in a zero waste community). That rubbish was mindless, just like all rubbish is, and it only becomes mindful when you're the person having to sort it out and think about where it all goes. It all goes into Great Big Piles of Crap.

I think we can do better than that.

So I did a lot of shitty work. And it offended me inside which was interesting. "This is manual labour," said my pride. "I am not a manual worker. I am a knowledge worker. Why am I hauling around sacks of crap like someone with no education?"

In the first week I had three dreams that senior members of my family - who have tried for me and have expectations of me - died and my silly actions were partly to blame. Last year a consultant writing think pieces for government strategy units: this year, a shit-clearing farmer. You're letting your family down, wasting all that has been invested in you, my guts seemed to be telling me.

But it was also interesting. I was grumbling to myself about spending a day hauling around canvas and bits of yurt, but then, some of the most amazing experiences of my life have happened in festival yurts that someone put up and took down. And I pay for my ticket, come in, sit in them, experience nirvana or something like it, throw my rubbish in the bin, fuck off, and people I never meet do the dirty work.

And food. My London housemate Mark wastes a bunch of food. If he ever buys vegetables, he makes one thing using some of them, and the rest go in the fridge in their plastic packets never to be touched again until they're mouldy and he or I or the Brazilian cleaner picks them up and throws them away.

Harvesting at Embercombe is inclusive. It involves all the vegetables. The criteria for inclusion is ripeness. If you're ripe, you're in. Harvesting for the Radford Mill farm shop involves a tonne of wastage. The criteria for inclusion is visual conformity to a norm. If the leaf is too big or wiggly or holy, it's to the house or the pigs or the compost heap - and a lot of it ends up in the compost because the house and the pigs between them can't eat all of the fresh ripe organic food that tastes amazing but never gets to the customer because it doesn't look pretty enough.

All of that, every bit of it goes out the window when you produce your own food. When you've invested in it, you love it. You won't let it be wasted.

Kim and I walked the mile and half back from the goat farm in the dark the other night, me carrying the three litre tub of milk we'd just taken gratefully from The Ladies. We walked a bumpy bridleway by starlight, slowly. We didn't want to drop the milk! If we spilt the milk, we really would cry! The whole no-use-crying-over-spilt-milk thing means something totally different if you have taken the milk from the creature with your own hand, and it is then to become the milk and yoghurt and cheese for your family for tomorrow / the day after / three days after respectively, and if you spill it, that's it! Effort wasted and a hungry(er) family. Something to cry over for sure - and avoid.

So. Where does this take us. Most people who eat food are many steps away from the people who make the food. So we value it much less and waste it a lot, and the growers get a shit job. And we get worse food because of the time-lapse between field and plate.

It's alright, it's not bad, some people get work, others get fed, that's good. But isn't is also much more miserable than it could be?

...

It's time to get specific. Growing food all day every day doesn't work for me. So what does?

1. Growing as headspace

If I've been doing office work for hours, there is nothing more fantastic than stepping away from the screen and the phone calls and the meetings and going into the calm space of Growing. You feel the sunlight and the air and you work manually with the sensual food factory, involving lush black earth, in harvest time handling gorgeous sensual colourful forms of food - food just picked beats an art gallery for me every time - in spring time preparing beds and carefully laying rows of seeds full of promise. It's slow, steady, measured, physical work in nature and it lets the head slow down and breathe.

That can be an end in itself, or sometimes, when I would grow food in the garden, I'd scramble my own head by working for hours and having tea and biscuits instead of actual breaks, then I'd go into the garden and slow down with the veg and ahhhhhh that's it. Your brain wanders around and gradually, new ideas bubble up, the problems you were caught on get unstuck, useful questions and perspectives just arise in your mind. You stop forcing and start letting, and everything starts to move again.

When you return to the screen, you do good work. Somehow you have been nourished.

Aside from work, just pottering in the garden with the radio on is great.

2. Growing as group headspace

There's a lot of value in working in the garden beside people you have important relationships with. Members of your team or family (I include partner in family), or your friends.

It brings space into conversation. And it slows it down. It's ok to pause for thought as you poke a hole in the ground and wiggle a tiny red onion into it, knowing it will come back a big onion.

Embercombe does this really well. Groups go and work the land together to talk and reflect and process and think slowly, at the pace of the garden, at the pace of the heart.

3. Growing as fun

On our first friends weekend at Embercombe, mark and I were asked to clean the outside of an entire polytunnel with a hose and a long mop/broom, which we did, while getting each other wet in the Autumn sun, playing around, being silly, shreiking with laughter, and teaching each other songs.

4. Singing and growing

Sometimes we started to sing songs while we picked together at the Mill. That was good. I reckon we should have fun fed singing sessions on the land while working it. Nice.

They do stuff like that in Africa.

Malidoma Some describes how it works in his village in Burkina Faso:

"Villagers are interested not in accumulation but in a sense of fullness. Abundance means a sense of fullness, which cannot be measured by a yardstick of the material goods we possess or the amount of money in a bank account...

"Most work done in the village is done collectively. The purpose is not so much the desire to get the job done but to raise enough energy for people to feel nourished by what they do. The nourishment does not come after the job, it comes before the job and during the job. The notion that you should do something so that you get paid so that then you can nourish yourself disappears. You are nourished first, and then the work flows out of your fullness.

"Many areas of work among villagers, including farming, are accompanied by music. Music is meant to maintain a certain state of fullness. People recognise that even if you are full before the work, you can't take that fullness for granted. You have to keep feeding it so that the feeling of fullness continues, so that the work you are doing constantly reflects that fullness in you. It is as if the output of work takes a toll on your fullness, even it if is an expression of your fullness, and you have to be filled again before you can continue. Music and rhythm are the things that feed someone who is producing something."

Malidoma Some, The Healing Wisdom of Africa, p68

So. Do I seem to be saying that:

Knowledge work and food making need each other. Knowledge work without land work is too heady and tight: land work without knowledge work is too dull

The participation principle rises again - it's good if you participate in making the food you eat, even a little bit

Growing works in community, in conversation, and with music, but not in isolation

So on the funny farm we'd have a garden that one person manages and the whole community and all it's visitors participate in a little bit. And musician gardeners / garden musicians get everyone singing. What about everywhere else? Maybe starting with getting it right on the funny farm is enough for now.

pic from rich66

pic from rich66